Liture, How I Manage My Reading Notes

Useful software often comes out of frustration. When a programmer finds themselves wondering about a tool or a library that doesn’t exist yet, they may decide to write it. At least, they know it would be useful for one user, themself, not to mention the fun of coding. In my case, I needed an easy way to navigate my ebook notes, and all I could find were subscription based services that didn’t fit my casual use. This is how Liture started.

“Readers eat books. Film eats viewers.” — The Wave in the Mind, Ursula K. Le Guin

One of the advantages of physical books is that we can write on the margins. That text filling the white space that the page offers has a name, marginalia, and it’s the old analog way to make that book copy feel ours. By writing on it we can enrich the text with our thoughts, and also highlight our favourite passages as well as the most crucial one to help us revise our reading later on. I tend to use a pencil, a ruler, and some coloured tags attached in the margin for quickly jumping to the best parts in the future.

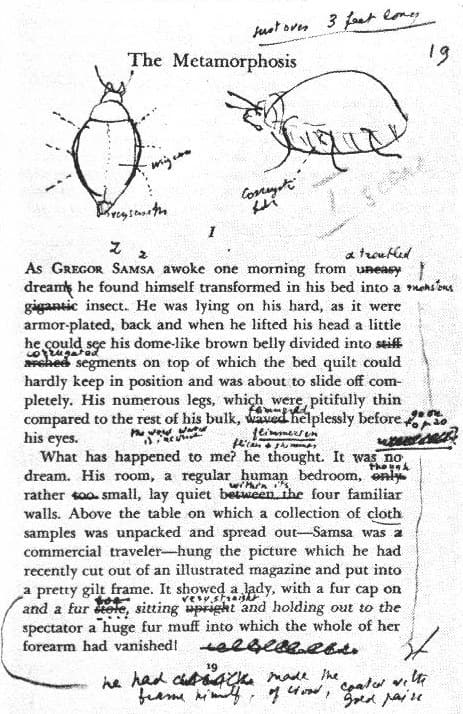

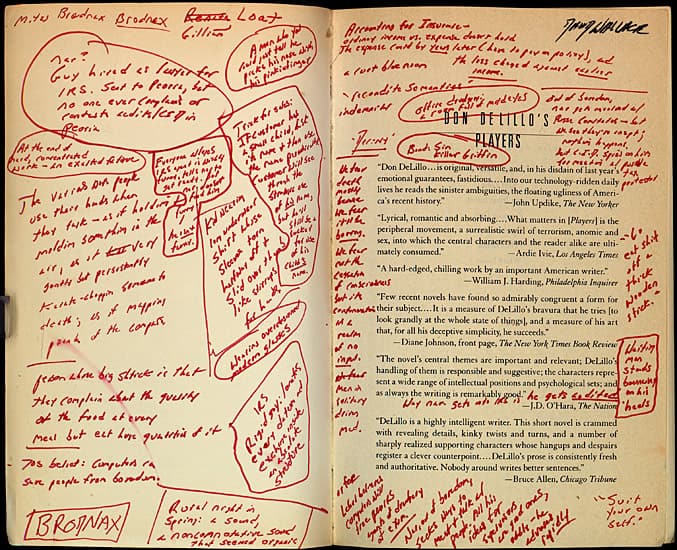

A lot of great writers in the past have used marginalia. Some of their book copies are still preserved, online we can see photos of the annotations made by names like Herman Melville, William Blake, Mark Twain, Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath, Jack Kerouac. I know that Vladimir Nabokov used to draw maps and object, since some of the original pages were printed on his posthumous book Lectures on Literature, like his annotated copy of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis. David Foster Wallace became famous for his heavy use of margin annotations. Some of his copies of Cormac McCarthy and Don DeLillo, filled with various notes, numbers and drawings, are kept exposed at the University of Texas in Austin.

I’ve read far more books recently than I did a few years ago, and I do most of my readings with an ebook reader. I love printed books. I miss the feeling that touching paper gives, the visual feedback of the progress, the different style for covers and typography used for each book. I still buy physical copies and often second-hand, but I prefer to read in Italian1, my original language, and since I’m in Australia, far from Italian bookshops and I don’t want to pollute the planet with my hobbies, I mostly read digital books.

I also have the habit of highlighting in books and sometimes taking annotations, which it’s easy using an e-reader. Soon my collection of quotes and notes had grown. For some books, like 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, I had to print my highlights to review them, filling around 15 pages, and then re-highlight the most important parts. Even if I find paper more effective for focus reading than digital text, I become frustrated every time I had to review my highlights and notes from an ebook, since I couldn’t find a way to access that data.

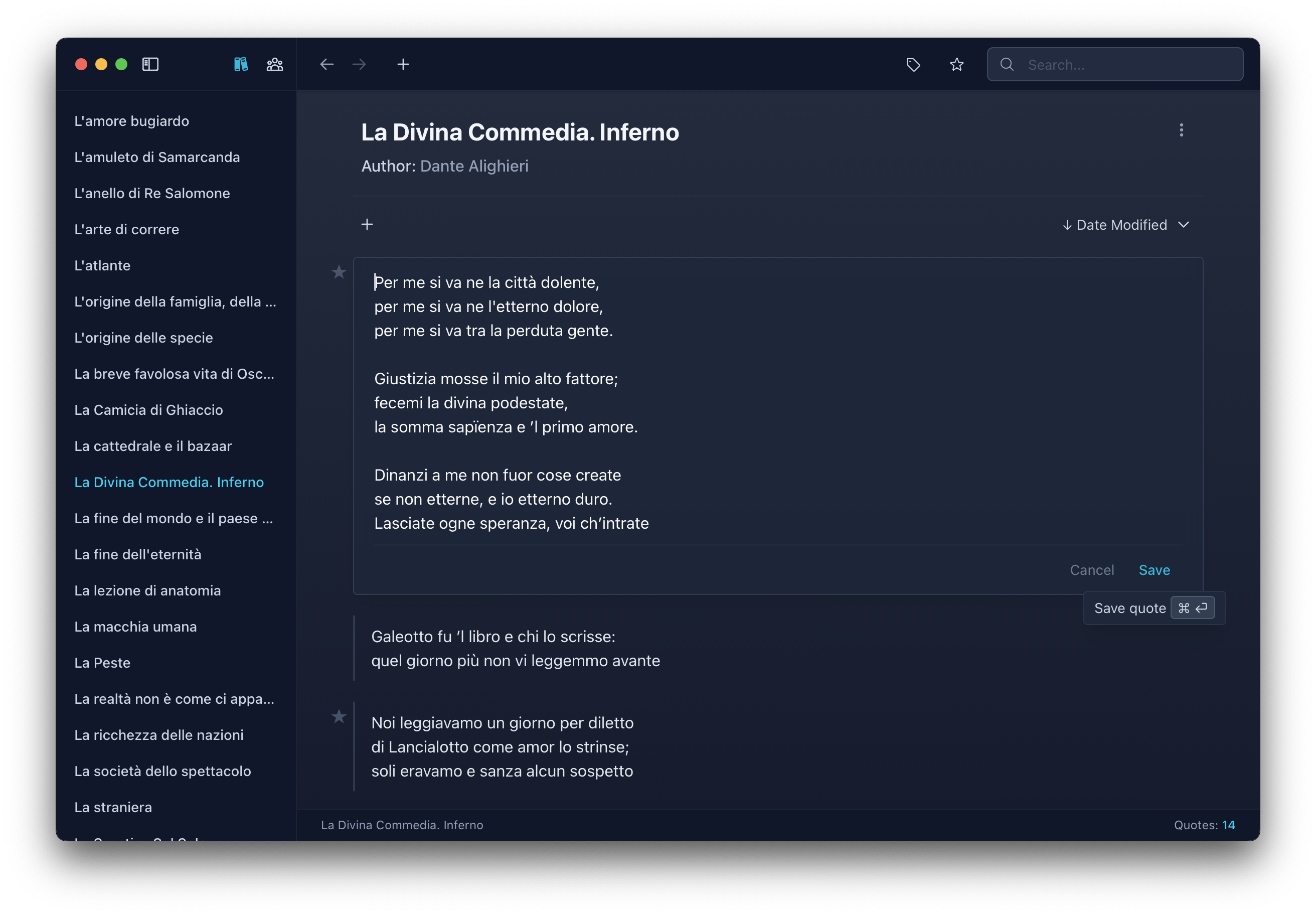

I use a Kobo reader and all the content that the user generates is stored inside the device. Export is not officially supported. A few years ago I started maintaining a python script that extracts highlights and notes in different formats, but with a lot of notes it stopped being practical. I needed a way to search my highlights and notes, to save my favourite quotes, to see them grouped by author and book. Also highlighting as well as typing on an e-reader is not that precise, the devices are usually quite slow to respond, so I ended up having a lot of errors and imperfection to fix. I want to edit my content, and also add new notes to enrich it. I needed a new kind of software for this.

Annotations on ebooks should mimic those on physical books; they have to be easily accessible and preserved. Keeping them stored inside devices in proprietary formats is dangerous. They can easily get lost. I started thinking that some of my book notes matter as much as photos of my past, they’re a part of my reading experience and I want to keep them for the future.

Kobo, Kindle, Apple Books, none of them facilitates exporting highlights and notes outside of their own platform, no common format exists for that. That’s where Liture comes helpful. It’s a desktop app to import and manage notes and highlights from the main three book platforms. The user can search and edit content, save the favourite items, and also manually add new authors, books, and notes. No cloud or subscriptions, free for all platforms. I’m using it to keep importing new highlights every time I sync my Kobo on my mac, and the content is automatically stored in a SQLite file that I regularly backup.

“There must be something in books, something we can’t imagine, to make a woman stay in a burning house; there must be something there. You don’t stay for nothing.” — Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

I think there’s a lot of potential for great software for readers, and still a lot to do. Big tech companies disregard reading and prefer to focus on more lucrative content, so readers are usually left with old platforms, not frequently updated, missing modern features, and often with incompatible formats. But it’s not all lost. Some groups of passionate readers are awakening and trying to fix the situation building new platforms and apps. I would like to do my part releasing Liture. Enjoy and make good use of it!

Footnotes

-

I tell others that I prefer Italian because I find the language generally more expressive than English, but in reality it’s because I fear I might forget it one day. So I read in Italian to keep the language from rusting in my head. ↩︎